Echoes 23. Dissection of an Immortal Melody

BY Asrar Chowdhury

Shout, The Daily Star, Thu Oct 30, 2014

http://www.thedailystar.net/shout/dissection-of-an-immortal-melody-47936

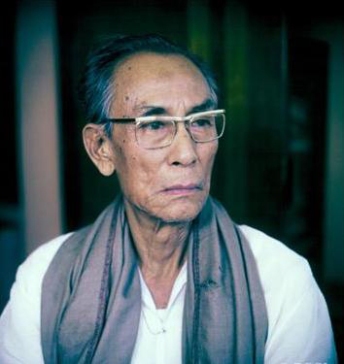

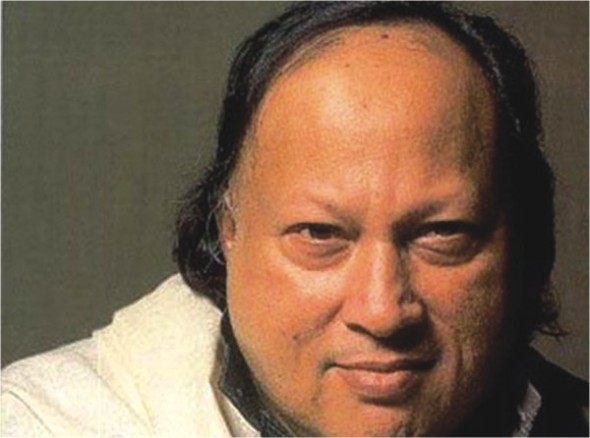

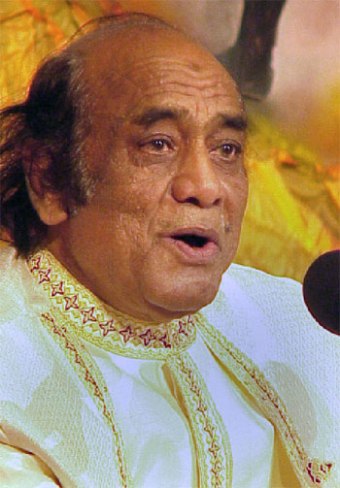

He couldn’t go back to Comilla where he was born and brought up. Calcutta didn’t give him his dues. Bombay was calling. With a deep sigh, the Prince headed off with his jhola of music. He took folk tunes from the Gomti and Homna rivers of his native Comilla. He blended them with special strokes (bol) of beats (taal) that were tailored for the singer and the mood of the song. To present his tunes to the genteel, he blended the folk tunes with classical music in thumri and kheyal. Through this Prince, bhatiyali from Bangladesh rocked South Asia. That was the mastery of Sachin Deb Burman (Oct 1, 1906–Oct 31, 1975), SD Burman to others and ‘Sachin Korta’ to us.

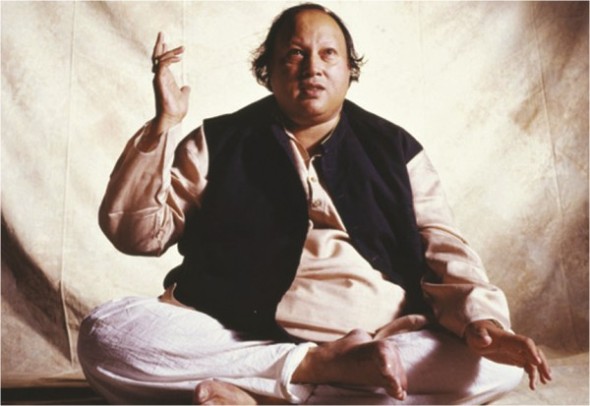

A melodious song synchronises crucial elements. The lyricist writes the song that rhymes in meters (chhondo). The composer adds a tune in an appropriate beat (taal). All songs need percussion. Different strokes (bol) on the drums will give different moods to the same beat (taal). The music director decides what instruments to use and how to place them in the song. The singer then tries to do it justice. The final instrument is one we seldom notice — the ear. In his biography, to Salil Ghosh, SD stressed the importance of listening. If the song is melodious, people will want to listen to it again.

He remains one of the most successful music directors Bollywood has ever seen. Through his music direction, Lata Mangeshkar, Asha Bhosle, Kishore Kumar, Mohammad Rafi and many others became timeless icons. SD would also record songs in his own voice, written by others, and usually composed by himself. He was well versed in an almost unseen combination of both Hindustani classical and folk music from East Bengal, today’s Bangladesh. From childhood in Comilla, he’d listen to music and its many subtle variations. It’s his ears that made his songs a timeless listening experience. Otherwise, with around only 135 Bangla recordings, it wouldn’t have been possible for anybody to define and re-define Bangla songs in the presence of Tagore and Nazrul. Let’s take Ke Jashre Bhati Gang Baiya from 1971, lyrics by his wife Meera Deb Burman.

Diaspora defines Ke Jash Re Bhati Gang Baiya. The lady is in a foreign land. She yearns to return to her father’s house downstream (bhati). The throwing of the notes; the timing of the beats; the strokes on the tabla; the instruments and their punching all had to be perfect within each section of a taal to give the listener the image of going downstream with the possibility of never seeing her father’s house again. SD uses the Komol Ni — the defining note of our folk music — to express the agony of yearning. While he comes down as if coming downstream, he uses the Komol Ga. The Komol Ga gives the feeling of getting lost in the waves of the bhati region. Structurally, the song then becomes based on Raga Kafi (with Komol Ga and Komol Ni).

There’s more to come. Ke Jash Re Bhati Gang Baiya is a song of a woman, but SD sings as a man. Did you ever ask yourself this question? The Bangla Re: Jash Re; Pran Kande Re; Nayon Jhore Re expresses all the agony from the soul and the soil. Each Re is hit with the note Ma. No line is sung the same way each time. There’s some subtle variation in throwing of the notes to avoid repetitiveness. This subtle variation is the melody. This melody is what’s made his music a timeless listening experience from his generation to the next and beyond.

If you go to Chortha, Comilla, find the Government Poultry Farm. Behind the farm you’ll see the remains of the palace of Raja Nabadwipchandra Deb Burman, father of SD. It was in this palace, SD was born. It was here that he was exposed to Bangla folk tunes and to classical music. It was from here that the seeds of the bhatiyali that later rocked South Asia were sown.

When the next generation fondly sings your songs, you know you gave back all you could to your birthplace.

Asrar Chowdhury teaches economic theory and game theory in the classroom. Outside he listens to music and BBC Radio; follows Test Cricket; and plays the flute. He can be reached at: asrar.chowdhury@facebook.com